(ITEM RUN COURTESY OF TIM LEONE, PATRIOT NEWS (PENN LIVE) on October 3, 2013) HERSHEY, PA – Martin St. Pierre, one of the AHL's premier forwards in the 21st century, last played for Mike Haviland more than five years ago.

When Haviland was named head coach of the Hershey Bears in June, St. Pierre quickly saluted the move on Twitter, expressing joy for his former mentor and lauding Hershey and Washington Capitals management for making an excellent hire.

“That's how strong I feel about the guy,” said St. Pierre, who will play for the Hamilton Bulldogs this season. “Hershey's lucky to have him.”

“I haven't talked to him in a long time, but I know that I can pick up the phone and talk to him and feel like we saw each other yesterday. He's that type of guy. He's definitely someone you want to look up to as a man and in the hockey world.”

Caps winger Troy Brouwer, who played for Haviland in the AHL and NHL, was a positive job reference when Caps GM George McPhee sought internal input.

“I just said that out of all the coaches I had, he probably had one of the biggest impacts on my hockey career since I was probably a little kid in my development,” Brouwer said. “Havy really treated me well.”

“He gave me a great opportunity when I was playing in Norfolk to be able to make the move to the NHL. He believed in me. And so with that, I've got to help him out as much as possible.”

In 2013-14, Haviland, 46, gets to establish fresh bonds of loyalty as he takes over in Hershey, the latest destination in a pro coaching odyssey that has made stops in Trenton, N.J., Atlantic City, Norfolk, Va., Rockford, Ill., and Chicago.

In print, the resume features ECHL Kelly Cup championships in Atlantic City (2002-03) and Trenton (2004-05), a 50-win season and AHL outstanding coach honors in Norfolk (2006-07), playoff appearances in all seven of his seasons as a head coach and a Stanley Cup as an assistant coach with the Chicago Blackhawks (2009-10).

In spirit, as evidenced by St. Pierre and Brouwer, the resume resonates with the power of positive testimony for a coach whose style is to empathize and deliver the honestly he desired as a player while demanding excellence.

“It's the atmosphere and the culture you create as a coach,” Haviland said. “I'm a positive guy. I like to teach. I like to communicate. I like to talk to my guys and let them know where they stand and what I expect out of them.”

“I think when your players leave and they won and they enjoyed playing for you and you got the best out of them, it's a win-win for everybody.”

The third U.S.-born coach in Bears history (Mike Eaves and Jay Leach are the others) joins a franchise where win-win is a must. Eleven Calder Cup banners in Giant Center hang as tradition and challenge.

Hershey's last three coaches – every coach since the Washington affiliation began in 2005-06 – has won a Calder Cup. And Bruce Boudreau (2005-06), Bob Woods (2008-09) and Mark French (2009-10) each did it in their first full season at the helm.

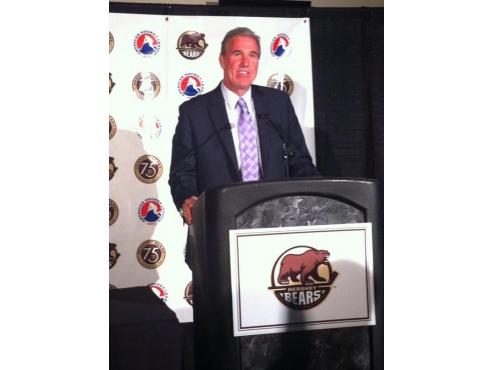

The halogen smile. The pugnacious bench demeanor. The coach-player rapport. The Jersey accent.

That is the personal formula Haviland will apply to a promising on-paper roster in a bid for Hershey's 12th Calder Cup.

“One of his famous sayings is, 'Call a spade a spade,'” said Rockford IceHogs head coach Ted Dent, who served as Haviland's assistant in the AHL and ECHL. “When you're doing well, he'll tell you. When you're not doing well and he needs more, he'll tell you, as well.”

“He's a great teacher. He's great at in-game adjustments. He's one of the best I've seen. He's a competitor. He wants to win and he makes sure he gets the most out of players.”

HOCKEY FAMILY

Haviland, born in Manhattan and reared in Middletown, N.J., comes from a pioneering Garden State hockey family.

His father, George Sr., played roller hockey and ice hockey, has been a top leader in state youth hockey for decades and has a youth championship – the George Haviland Cup – named in his honor. Older brother George Jr. and younger brother Richard both are longtime New Jersey youth coaches, and George Jr. also owns rinks.

“And a mom,” Haviland said, “that probably knew more about hockey than all of us.”

Margaret Haviland watched her middle son leave home to play Tier 2 junior hockey in Oakville, Ontario, at 15 in 1982. It was rare for a U.S. kid to make such a move at the time.

Haviland lived with a billet family and wore a figurative red-white-blue target on his back as the lone American in the league. Practices were a constant and often literal scrap for every inch of ice, but through four years he ultimately earned his stripes as captain.

“A big eye-opener for me,” Haviland said, “on how the game should be played and was going to get played.”

Such an eye-opener that he initially thought he'd made a mistake and called George Sr. to ask to come home.

“My dad said, 'No, we made a commitment and you're staying,'” Haviland recalled. “And he hung up the phone. A little tough love. Certainly, it was the best thing for me.”

An opportunity to play at Cornell fell through late, so Haviland ended up at Elmira College and earned All-America status in a powerhouse Division II program that played before crowds of 5,000 in the hometown of Heisman Trophy winner Ernie Davis and the burial place of Mark Twain.

Brian McCutcheon, who would go on to coach Cornell, the Rochester Americans and serve as an assistant with the Buffalo Sabres, was his first head coach and he finished under Glenn Thomaris.

The lanky 6-3 winger produced 27-24-51 in 23 games in 1989-90.

“I could defend myself,” Haviland said. “I didn't just go look for it. I played the game hard, but I also was a scorer.”

After his senior year, Haviland had a two-week camp tryout with the Boston Bruins, signed with the Hartford Whalers and played four games for the AHL's Binghamton Whalers in 1989-90 before discovering he was actually eligible for a supplemental NHL draft.

The New Jersey Devils took Haviland in the first round (15th overall), but there would be no storybook rise to his home state NHL team. The rest of his pro playing career, ended by a right shoulder injury, consisted of 16 ECHL games with Richmond and Winston-Salem in 1990-91.

Always a student of the game – Haviland said he used to intently study Don Maloney when his family attended New York Rangers games at Madison Square Garden – the young retired player returned to Elmira College to finish a marketing degree and begin his coaching career under Thomaris.

After three years at Elmira, though, Haviland took a brief detour out of the game. He became a route salesman for Sunshine Biscuit, Inc., hawking cookies and Cheez-Its, but that lasted about 18 months until he turned in the company car.

He realized he was a hockey guy whose passion could only be satisfied by the game. He was a hockey coach who set a goal to someday rise to become an NHL head coach.

“I believe,” Haviland said, “anybody can do anything.”

ECHL ENTREPRENEUR

The ECHL is an entrepreneurial league for coaches. They wear numerous hats: coaching, player recruitment, immigration issues, marketing.

After two seasons as an assistant in Trenton, first under former Caps head coach and current Providence Bruins head coach Bruce Cassidy and then under current Abbotsford Heat head coach Troy Ward, Haviland got his first head coaching shot with Atlantic City.

“You do everything,” Haviland said. “That league prepares you as a coach because you have to be prepared. If you're not, you're not going to win down there.”

He won the Kelly Cup his second season and repeated the feat two years later after moving back to Trenton as head coach. Winning ECHL titles in two places was an especially telling affirmation of his coaching ability and launched Haviland into the AHL as Norfolk's head coach in 2005-06.

“He wears his emotions on his sleeve,” said Trenton, Norfolk and Rockford assistant Dent, who had training camp stints with the Bears in the 1990s when he played for the ECHL's Johnstown Chiefs. “The players always know where he's at and what he's thinking, and he'll tell you. In rough stretches, when you hit the bottoming point, then he bursts. There's been a lot of times that would be a spark that turned things around.”

St. Pierre's first full pro season was with Norfolk in 2005-06. Focusing on offense and not an all-around game, the rookie made a stupid first-period play that cost an early-season goal.

He sat on the bench for the second and third periods. It was some George Sr.-style tough love.

“He was definitely sending a message to me and to the other guys that it doesn't matter who you are on the team,” St. Pierre said. “If you don't want to listen to what he is portraying for a system and take care of the defensive zone, then you're going to sit on the bench. The next day, I remember coming to the rink and he was the first one to greet me at the door and say, 'Let's go talk in the office.' He just sat me down and he went over everything.”

“He's proven a point. The next day, he wants you to correct it and not make it happen. I went on to have a great season, a great second half from there. We joked about that the last time I saw him.”

Haviland's Norfolk years from 2005-07 featured strong regular seasons that ended in first-round playoff exits. Boudreau's Bears swept Norfolk in 2005-06.

“Him and Bruce Boudreau used to just scream at each other on the benches when Bruce was in Hershey,” Brouwer recalled. “Those were always pretty entertaining.”

In 2007-08, Chicago switched its AHL affiliate from Norfolk to Rockford. In a situation that was a smaller-scale version of the Cleveland Browns relocating to Baltimore to become the Ravens, Haviland and his team moved to Illinois.

The season began with a road-heavy schedule and a home building that was still under renovation. That team won 44 games and lost a seven-game, second-round war to eventual Calder Cup champion Chicago.

“We had to roll with the punches, form a team, get the guys on the same page and start to win some hockey games,” Dent said. “We ended up having a really good group that year.”

WILL POWER

A personal reckoning came for the onetime svelte power forward in August of 2009 before his second season as an assistant coach with the Blackhawks. There had been years of long bus rides, bad diet habits, no workouts.

Haviland stepped on a scale. It read 302 pounds.

“I hit a number I thought I'd never hit in my life,” he said.

“I never thought of myself as that person who would hit 300. I always thought it would be somebody else. It would never be me. So it was a little reality for me.”

A training regime and healthy diet plan ensued. As the Blackhawks grew into NHL champions during the 2009-10 season, Haviland shrunk by 65 pounds on the way to eventually losing 100.

“Everybody who's close to him, we're all very proud that he was able to do what he did and put his mind to it,” Dent said.

“I remember talking to him about it. It was all about his eating habits and he started to exercise. The combination of those two things really turned it around and he was able to turn it around and lose a lot of weight. Then he had to go and buy a whole new wardrobe, which was a good thing.”

Haviland also has succeeded at the greater long-term challenge of keeping off the weight. He keeps old pictures and old suits as a reminder and said he currently runs in the 203-205 range.

“It just snowballed on me and got out of control,” Haviland said. “I'm a driven guy. When I put my mind to something, I can tune it out.”

In Chicago, Haviland found profound hockey nourishment when he landed in the orbit of coaching legend Scotty Bowman, the Blackhawks' senior advisor for hockey operations whose son, Stan, is the club's general manager. He cites Bowman, Thomaris, Ward and Blackhawks head coach Joel Quenneville as seminal coaching influences.

During the summer, Bowman personally approached McPhee to commend him on the selection of Haviland as Hershey's coach.

“I've become very close to Scotty and talk to Scotty on a regular basis,” Haviland said. “You always look up to the winningest coach, I believe, in all sports. He's somebody I lean on, rely on.”

“I was fortunate to work with him all those years and become friendly with him. To gain his respect in the hockey world, I think, is irreplaceable.”

Those Chicago years ended following the 2011-12 season, when Haviland exited after Quenneville shook up his staff.

Haviland interviewed for Washington's head coaching job in the summer of 2012 before landing back in Norfolk as associate coach with head coach Trent Yawney. The positive residue of that Washington process led to his Hershey hiring a year later.

BENCH SWITCH

In the wake of Haviland's jousts on the visiting bench during his head coaching tenure in Norfolk, there is irony in him setting up shop on the home bench at Giant Center.

Las Vegas doesn't put out an over-under number on predicted bench minors for an AHL head coach. If it did, Haviland's might be set around two for 2013-14.

“I'm trying to calm down in my older age,” Haviland joked.

“I'm a fiery guy. I always have been. My players are going to know I care about them. I'm going to back my players.”

There is a switch that clicks when Haviland hits the bench, going from off-ice voluble to in-game warrior.

“I can be the nicest guy in the world off the ice,” Haviland said. “When we're behind that bench, it's business.”

The very early returns in Hershey have been positive.

Said Bears President-GM Doug Yingst: “I like how he's a dominating force.”

Said veteran Bears centerman Jeff Taffe: “I like how he says you can't take anything for granted. I think he instilled that right away. … He brings a great attitude. He's smiling. He wants to get to know you. I think that goes a long way with guys.”

It is a pattern that would be familiar to St. Pierre.

“I've seen him develop relationships with players, especially me, that it kind of correlates into the on-ice,” St. Pierre said. “You respect him as a coach. You know the door's always open as far as going to sit down and talk about ups and downs or whatever is on your mind that day. Then again, he's the type of coach that you want to go on the ice and win hockey games.”

“I just turned 30 and I still apply what I learned from him about hockey and the [pro] lifestyle.”

As much winning as he has already done, Haviland knows there must be more. The NHL head coaches club is a tough one to crack for aspirants who don't have an NHL playing pedigree.

“Hopefully, he succeeds down there,” Brouwer said. “I know he would love to be able to come back to the NHL one day. I hope good things for him.”

The regular season and the playoffs offer the gauntlet of a tricky new puck sales route in Hershey.

Haviland said he views himself sort of like a business owner whose office is a 10,500-seat arena. Treat your employees right, hold everybody accountable to the same standards regardless of roster status, and they'll treat you right and won't cut corners.

To accomplish that, a coach must know his players, know when it's time to give them a kick, know when it's time to lay back and give them them a day off.

Haviland's mastery of that human calculus has landed him in the best coaching job outside of the NHL.

“I'm very fortunate – and I know that — to be where I am in the game,” he said.

How tweet it is.